It’s A Wrap

One of the many ways in which Uganda’s court management structures differs from ours is in its heavy use of Registrars – lawyers who aren’t yet judges (but who will be in the future) exercise a fair number of judicial functions. For example, the Criminal Court does most of its work in sessions – groups of forty cases that are scheduled for trial over the course of forty days. The Registrar chooses which of the thousands of prisoners “on remand” will be “cause listed” for that next session. A case being cause listed triggers the right to have an attorney appointed for those in the session. The money allocated for the session (40,000,000 shillings, about 13K USD) is sent to the Registrar to administer. 1M goes to the judge, 500,000 to the Registrar, 250,000 each to the judge’s body guard and driver, about 10M to the lawyers for the forty defendants, etc. Those who allege corruption occurs in the administration of justice often point to the relative trust placed in the Registrars when the session funds are released.

For nearly two years, there was no substantive Chief Registrar – the one supervising the various Registrars. Vacancies in important roles litter the Ugandan judiciary, including in the Supreme Court (about five), Court of Appeals (about eight), and in the High Court (about thirty). But last year – just before we began our prison pilot project, Paul Gadenya was moved into this position from his post as Chief Technical Advisor of the Justice, Law, and Order Sector (umbrella organization over eighteen different departments affecting law and justice (judiciary, prisons, police, prosecution, department of justice, etc.)). As Chief Registrar, Paul basically runs the trial court system and is fourth in the official judicial hierarchy below the Chief Justice, Deputy Chief Justice, and Principal Judge, which is why we wanted to interview him for the documentary, so he could reflect back upon the progress toward implementation of plea bargaining that had been made since last summer.

As I knew he would be, Paul was terrific. He is really smart, thoughtful, and well-spoken. He doesn’t sugar coat the challenges Uganda faces, but remains optimistic about the future of his country and about its full-scale integration of plea bargaining. He reported that since the Pepperdine prison project involving 160 cases at Luzira last summer, more than one thousand additional cases have been plea bargained by Ugandans, and the momentum is building to increase the pace.

After Paul, the crew filmed Andrew Khaukha, who works for both Paul and the Principal Judge to implement their vision of country-wide plea bargaining. More than anyone, Andrew is making this happen with his dogged determination and strategic planning. His will be an important voice in the film.

After we watched the rough cut of the documentary that was prepared after last summer’s filming, it became clear that the last chapter of the story was missing. There needed to be an answer to the question raised by several of our students – sure, we interviewed 160 prisoners and prepared case summaries, but what would happen after we left? Would these prisoners really get the access to justice they sought? Would there be any lasting change?

These questions were partially answered by the interviews we captured in which the talking heads told us how much difference we had made, but what wanted even more than these answers were stories of real prisoners who had benefited.

So from the High Court, we returned to the Luzira prison complex where most of last summer’s filming took place. This complex houses Luzira Upper, which is the maximum security prison, Murchison Bay, the medium security prison, and Luzira Women’s, where about four hundred women are on remand or serving out their sentences for violent crimes. Last summer, we prepared 160 combined cases from all three prisons, though we filmed exclusively at the maximum security prison.

During my prior visit to Uganda about three months ago, I had attended a consensus-building workshop at which the latest draft of the plea bargaining practice directions (guidelines) were being discussed. At this meeting, one of the prisoners from Murchison Bay named Rashid had been asked to speak about what plea bargaining meant to him the other prisoners. I had been blown away by the clarity with which he articulated the reasons he and his fellow inmates benefited from plea bargaining – reasons that went well beyond the fact that he received a shorter sentence than he feared if had gone to trial. He explained that the uncertainty of not knowing when, if ever, he would go to court, not knowing when, if ever, he would get a lawyer, and not knowing when, if ever, he would be released was crippling him and his fellow inmates socially, psychologically, and spiritually.

When he was finished speaking at that workshop, I knew we needed to interview him for the film. With Andrew’s assistance, we secured permission to go to Murchison Bay to ask the warden if we could interview Rashid for our film. Fortunately, the warden (Savestino) had been with me in Louisiana two months ago for a study tour of best practices in moral rehabilitation. He was also eager for plea bargaining to continue because he saw firsthand the positive impact on prison morale, so he readily agreed to allow us to interview Rashid.

Because Rashid had read from a prepared text a few months ago, I wasn’t sure how well he would be able to tell his story without reading it. When they brought him to the warden’s office, his eyes lit up when he saw me. When I introduced myself, he smiled and said, “I know who you are – you came here to tell us about plea bargaining more than a year ago before the team of lawyers came last year. I also saw you at the conference at the country club.” That was a good sign. I told him we wanted to ask him some questions and I asked him if he still had his notes from when he spoke. He again smiled and said in perfect English, “I have it all in my head – I can talk about it all day long.”

The interview went exceptionally well. He nailed every question and explained that he is so excited to be reunited with his daughter on March 23, 2019 – he is counting the days now that he has a release date.

Rashid embracing his future (Photo by Rob Hauer)

Andrew had also told us that two women we had interviewed at Luzira Women’s Prison had been released during the last year. Both had been resettled to Mubende, about three hours from Kampala. Our hope on Friday was to track down one or both of them so they could tell their story of how the plea bargaining program set them free. But in order to do this, we needed to capture a slice of life in the women’s prison, which we didn’t have time to get last time, in order to set up the contrast. So we got permission from the warden there and filmed about an hour of daily life at this prison. As we were about to leave, we heard some faint singing coming from one of the cell blocks, so we went to investigate. Ten minutes later, we were in the middle of the cell block surrounding by fifty jubilant women dancing, playing plastic drums (using a bucket), and singing their hearts out about their Savior who rescues them. We recorded for about fifteen minutes, then shifted to the next cell block over who wanted us to record them singing. We now have a soundtrack for the film that is causing me to tear up just writing this as I remember the passion and joy in their eyes and their voices.

Thursday night, I had dinner at my favorite restaurant with our Pepperdine students, who were finishing their summer internships the next day, and our Nootbaar Fellows, who will be in Uganda for another few months. (Earlier that day, I had another productive meeting at the US Embassy about possible funding for some of the projects we are working on).

Farewell dinner with the Pepperdine Interns

On Friday morning, we completed our final interview, which was of the Principal Judge, who is the Chair of the Plea Bargaining Task Force, and the architect of the nation-wide roll-out of plea bargaining. As always, he was clear and determined, and grateful for the partnership between our institutions.

At about ten, we set out in search of the two women who had been released. By four, it was clear we wouldn’t find them, even with the help of a local prison officer. We did get the phone number of one of them, who told Andrew that she had relocated to Wakiso, about forty-five minutes outside of Kampala. We decided to reload and renew our search on Saturday morning, but time was running short, as we were set to fly home Saturday evening.

At 1:00 a.m. Saturday morning, Henry arrived into Kampala after finishing his final examination of his first year of medical school that afternoon in Ishaka – six hours away. We chatted for a few minutes before catching a few hours of sleep in advance of setting out for a second day of searching for the released prisoner.

By 10:00 a.m., we had found her. She was thrilled to see Andrew, whom she remembered from his many trips to the prison informing her and her fellow inmates about plea bargaining. Since being released from prison, after spending four years on remand, she had been “born again” and was serving as an associate pastor for her village church. She was also reunited with her nine-year old daughter, from whom she had been estranged prior to being arrested for her minor involvement in a mob killing of a thief. During the plea bargaining program, she had pled guilty to manslaughter (she hit the deceased with a stick after a group of male villagers had beaten him thoroughly – he died a few days later), and was sentenced to time served. Needless to say, she was thrilled to be out and living a new life.

Christine telling her story (Photo by Rob Hauer)

After the on-camera interview, we found out what her monthly rent was and paid three months’ worth. She was exuberant and sang a song, along with a few others as back-up, called “Webale Jesu” – Thank You, Jesus (for Redeeming Me). Her voice was almost as beautiful as the lyrics. It was a rather emotional moment, to say the least. My prediction is that the film will end with her singing this song.

Webale Jesu

Following Christine’s interview, we drove to the Wentz Medical Clinic where my family assisted the Gregstons (our Twin Family) in 2012, and where my two youngest helped a few weeks ago. The crew shot some “B-roll” of Henry walking around in his lab coat to show that Henry is now entering the clinical stages of his medical training. When we finished filming last summer, Henry’s goal to attend medical school was just a dream, so capturing him a year later as an actual student closes the loop in a very uplifting way.

Just before we left, Michelle Abnet (Revolution Pictures Producer) had the idea of taking a couple pictures with the wood carvings I commissioned when I arrived in Uganda three weeks ago, and had received back the night before.

“Remand” is the title of the documentary.

It was so great to spend the day with Henry again, and to be able to celebrate in person his exoneration on all charges that had been pending for over five years. Our dear friends, Colin and Amy Batchelor, had sent with me some money to allow Henry to have a proper celebratory party with his family on Saturday night, which is the first time he will have seen them since we received the favorable ruling three weeks ago.

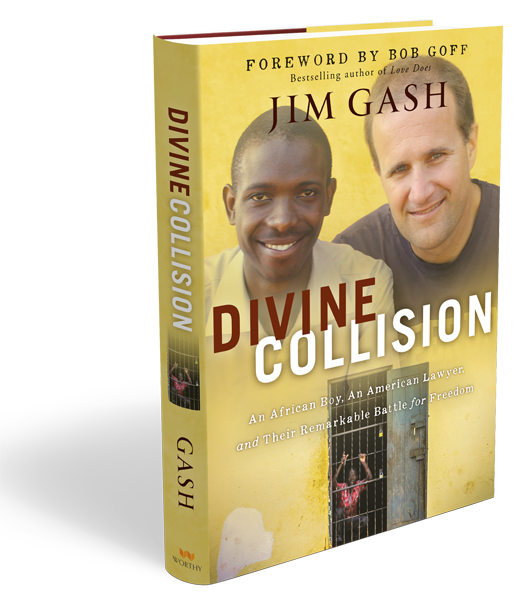

Thanks for following along. My final edits on the book (“Divine Collision”) are due in about a week, and the publication date has been set for January 26, 2016.